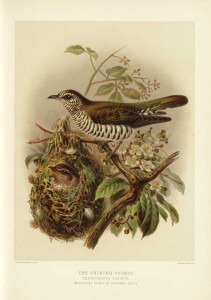

The shining cuckoo, pipiwharauroa, is one of two kinds of cuckoo that are native to New Zealand. The other is the long-tailed cuckoo, koekoea. The shining cuckoo is about the size and weight of a sparrow. The long-tailed cuckoo is more than twice the size and five times the weight of the shining cuckoo.

Both species are found throughout the forests of mainland New Zealand and some offshore islands. They are only resident in Aotearoa during spring and summer. They come here to breed, and afterwards they migrate north to the tropics—especially the Solomon Islands,Papua New Guinea and Indonesia—where they spend the winter.

For a bird the size of the shining cuckoo, that’s no mean trip—around 5000 km—and usually involves a stopover on the east coast of Australia. Australia has its own shining cuckoo, closely related to ours. The scientific name of both species is Chrysococcyx lucidus, which literally means “gold cuckoo shining.”

Shining cuckoos arrive in the North Island in mid to late September, and show up in theSouth Island a few weeks later. They eat insects, spiders and other invertebrates. Two of their favourite insects are the small green caterpillars of the kowhai moth (which feed on kowhai leaves) and the hairy black caterpillars of the magpie moth, which feed on ragwort and cineraria. Magpie moth caterpillars are sometimes called “woolly bears” because of their bristles. Most other birds find these caterpillars unpleasant to eat, or even poisonous, which leaves all the more for the cuckoos.

Like many species of cuckoo around the world, the shining cuckoo lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, and takes no part in raising its chicks. This behaviour is called brood parasitism. The shining cuckoo almost always lays its eggs in the nest of the grey warbler, riroriro (the host), or, on the Chatham Islands, the closely related Chatham Island warbler.

Riroriro is a tiny bird, smaller than a waxeye, and weighs less than a garden snail. It is the only bird inNew Zealandthat makes an enclosed, waterproof nest. The nest is pear-shaped, with a small entrance on one side. People have long wondered how the cuckoo gets its egg into the nest. The nest hole is less than 3 cm in diameter, and a cuckoo would have a hard time squeezing through that gap. It was commonly thought that the female cuckoo must lay her egg on the ground, or a tree stump, then pick it up in her beak and “post” it through the nest hole. But recently a cuckoo was caught on film entering the nest, head first, laying the egg, then squeezing back out again. Grey warbler nests are very well constructed so can probably withstand the stretching that occurs when the cuckoo invades it.

Once the egg is in the nest, the female cuckoo removes one of the warbler eggs, so that when the grey warbler mother returns to the nest she will find the same number of eggs as when she left—except one of them will be larger than the others, and a different colour. Perhaps in the darkness of the nest the grey warbler mother doesn’t notice the difference, for she is happy to sit on all the eggs regardless.

The cuckoo egg always hatches first. When it is a few days old, the cuckoo chick pushes all the remaining eggs and any warbler chicks that have hatched out of the nest. Now the grey warbler has only one chick to feed, and a very noisy and insistent chick it is. How does it continue to fool the grey warbler parents? One way it does so is to mimic the “feed me” begging call of the grey warbler chick. The two calls are almost indistinguishable (see below). The cuckoo chick makes such a pathetic begging sound—eee, eee, eee—that not only the grey warbler parents, but also other passing birds, such as fantails and robins, seem unable to resist feeding it.

Shining cuckoo chick:

Grey warbler chick:

Shining cuckoo adult:

Grey warbler adult:

The cuckoo chick leaves the nest at around four weeks, and starts to feed itself. At the end of summer it is ready to make the long flight to the islands of the western Pacific—a place it has never seen. A few shining cuckoos overwinter in New Zealand, but they are the exception; most spend the winter in the tropics. They will return when they are two years old and ready to breed, and after that they migrate every year, always returning to the vicinity of where they were raised.

How does the grey warbler cope with having its clutch destroyed by an intruder? Not too badly. Many warblers raise a clutch of eggs in August or September, before the cuckoos arrive. It is only their second clutch of eggs that will be lost if a cuckoo infiltrates their nest. And grey warblers have learned to cope quite well with urban environments, and are often seen around gardens, whereas shining cuckoos are more restricted to patches bush. So although individual grey warblers may lose a breeding opportunity, the species is not at risk.